Code of Hammurabi

Hammurabi

- Hammurabi was one of the best-known kings of the Babylonian Empire. Under Hammurabi, Babylon gained more control over Mesopotamia. But one of his most important achievements was the ‘code of Hammurabi’.

- The code was written so that people would respect each other and behave in a decent manner. It is still the first written record of laws in human history. People were reminded of the need to obey the laws and they were on public display for everyone to see on stone pillars called steles.

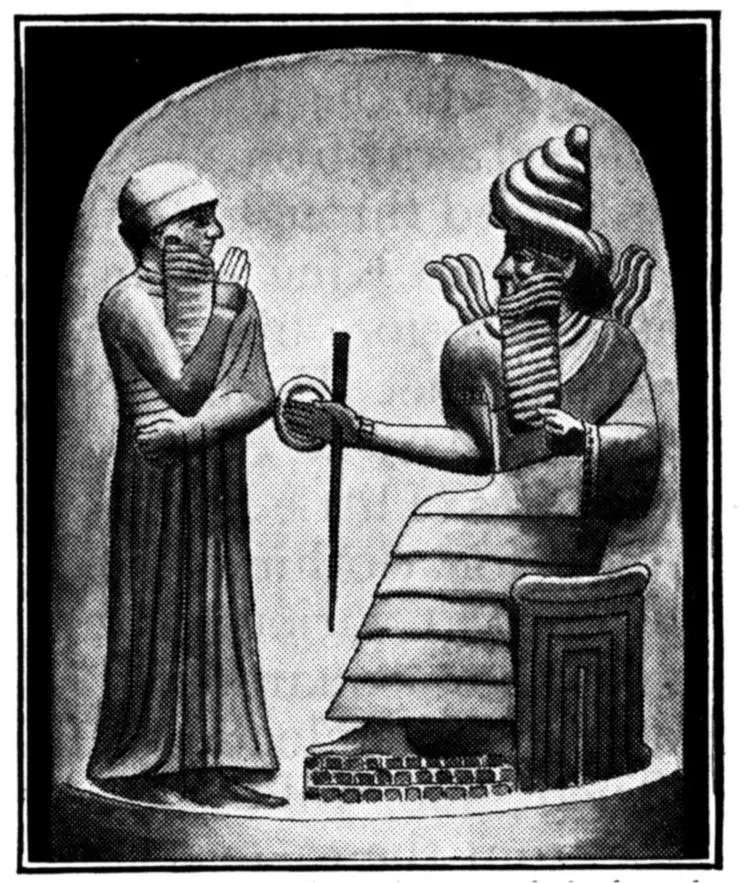

- The original black stone stela with Hammurabi’s Code carved into it was made from a four-ton slab of diorite. Diorite is an extremely hard type of rock so carving the code would have been very tough work.

- The top of the rock features an image of Shamash, the Babylonian god, handing over the law to Hammurabi. The rest of the monument contains the detail of the laws.

What does the code contain?

- Hammurabi’s code consists of 282 laws that specify a range of possible crimes and the punishments that will be received by those who commit those crimes.

- For example, the code forbids typical crimes of the time, such as the theft of an ox. For this crime a person would have to pay back 30 times its value. A son who hit his father could expect to have his hands cut off. The chopping off of hands was a common punishment and this still exists today in countries, such as Saudi Arabia.

- Hammurabi’s Code is famous for its belief in “an eye for an eye”. This means that if a person is injured or harmed, the person responsible should receive a similar injury or punishment. For instance, if a man were to break another man’s leg then the same injury would have to be inflicted on the man who committed the crime.

- More serious crimes, such as murder, could lead to a number of equally gruesome punishments. Many people who carried out such an act were impaled on a stake.

The laws and society

- The laws in the code reflected the needs of Babylonian society. Due to the importance of agriculture and trade in ancient Mesopotamia, laws on matters, such as water control, were common in the code. If farmers allowed their land to be flooded and affected the crops of other farmers they would have to pay them for the loss.

- Most of the laws in the code covered marriage and the family. Parents would set up arranged marriages for their sons and daughters and the bride and groom would sign a contract.

- The laws worked heavily in favour of the man in any given marriage. If he wanted to divorce the wife he could do this quite easily. The law code made it much more difficult for a woman to do the same.

Social class/men and women

- In reality though, the “eye for an eye” approach was not always applied in practice as the punishments often depended on the social background or gender of the person who committed the crime.

- If a person from the upper classes injured a person from the lower classes rather than receiving a similar injury that person would probably get a fine instead.

- The law was applied differently for men and women. If a man had a relationship with another woman outside his marriage, this was accepted. If a woman did the same, she would be thrown into a river and left to drown.

- These examples show us why the code is so valuable because it tells us so much about what life would have been like in ancient Babylonia.

Lasting effect of the code

- Hammurabi died in 1750 BC and his empire soon declined but the code remained important as a guiding document in Mesopotamia for many years to come. Empires that followed used many of the laws as a basis for their own systems of justice.

- Hammurabi’s law code put in place some basic legal ideas that still exist today. For instance, it contains a section that states that a man is “innocent until proven guilty” which means that anyone who has been accused of committing a crime must be presumed innocent until they have been proved guilty. This idea is so important that it is now seen as a basic human right.

- The law code also laid the basis for the idea that if people had a serious disagreement they could present their evidence to a judge. They could also draw on witnesses to help their case in much the same way as we do in courtrooms today.